By Jenn Fang

Northwest Asian Weekly

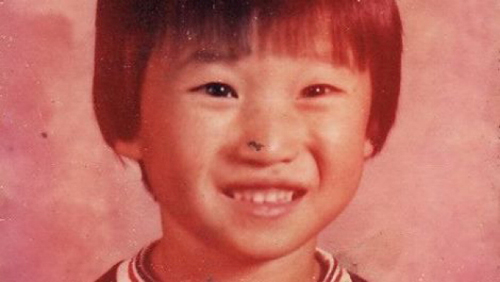

Adam Crapser as a child

By his own admission, Adam Thomas Crapser has had a difficult journey; but through it all, he has worked hard to create what he calls a “a semblance of a ‘normal’ life”.

In 1979, Adam arrived in the United States with his older sister as a transnational and transracial Korean American adoptee. Through most of his childhood — and through two placements — Adam was forced to endure unspeakable physical and emotional abuse. In 1991, Adam’s adoptive parents, Thomas Francis Crapser and Dolly-Jean Crapser, were arrested, charged and ultimately plead guilty to multiple counts of child rape, child sex abuse, and child abuse.

Adam is a survivor of the Crapsers’ violence.

Adam’s life bears the scars of that torture and what it took to survive; but, Adam has emerged today as a married father of three, with a fourth child due in May. He is, by all accounts, living that “normal” American life.

Yet, that’s not how the federal government sees it. In January of this year, the Department of Homeland Security served Adam with deportation papers. In just one month, Adam will face a hearing regarding deportation to a country he has never known.

In an interview with Gazillion Voices Radio, Adam Crapser recounts his story. Adam arrived in the United States with the name Shin Song Hyuk in 1979 at the age of four and was adopted with his biological sister by a Michigan family headed by Stephen and Judith Wright. Adam lived with the Wrights for five years, where he faced multiple acts of physical and sexual abuse. Adam says, “this would be my earliest memories of violence and social/sexual dysfunction.”

In 1986, Adam and his sister were relinquished by the Wrights to Child Services, where they were separated from one another. Adam lived in a group home in Oregon for a year before being formally adopted by the Crapsers, who along with one of their biological sons, subjected Adam and seven other foster children — all aged 6-13 – to years of abuse and torture. Adam says in an interview with Gazillion Strong:

During the five years that I lived there with them, every day it was pretty common to be choked from [the elder Crapser] or beat or hit or burned or some form of heinous, heinous, sadistic abuse.

Specifically, I mean, I could go into very memorable experiences I have that stand out for various reasons. For instance, he broke my nose at age 14 because he couldn’t find his car keys, and to this day I have a crooked nose for it.

In 1991, the Crapsers were arrested and convicted of sexual and physical abuse; both accepted plea deals to serve 90 days in jail and pay fines for their crimes.

Meanwhile, Adam grew up a troubled teenager, and ran afoul of the law a few times related to misdemeanor crimes (most petty theft), and all associated with maintaining his own survival. By his own admission, Adam has made “bad choices”, but most stem from being forced to endure a string of terrible situations. Adam describes the circumstances surrounding one theft charge (edited for grammar and clarity):

I was homeless and learned many things about myself and life at this age. At this time I broke into the Crapser’s home in Keizer, Oregon. I did this to retrieve my Korean bible and rubber shoes that came with me from Korea. The Crapsers had refused to return anything that belonged to me or help with my naturalization.

This happened when I was 17. I was charged after I turned 18 with Burglary in the 1st degree. I was convinced by the Crapsers — as well as by the State’s public attorney — to take the plea bargain and get 18 months probation. I agreed.

It turns out that both the Crapsers and the Wrights committed one final act of neglect against Adam: they never completed his naturalization paperwork.

For those of us who are not transnational adoptees, it may come as a surprise to learn that until recently, American citizenship was not automatically granted to transnational adoptees upon arrival in America. Until 2000 — and unlike the biological children of American citizens born overseas (who receive American citizenship by birth) — adoptees were forced to undergo the same lengthy immigration process that adult immigrants face. But what happens to adoptees whose parents don’t complete the naturalization paperwork for their foster children? Adam says of his own experience:

On more than one occasion I have asked the Crapsers over the years why they never naturalized me, I was always told, it was not their responsibility.

For adoptees who were placed with abusive (or just ignorant) foster families who fail (or refuse) to sponsor the naturalization of adoptees, this legislative loophole could lead to the predicament now facing Adam: living as an undocumented American for most of his adult life, Adam struggled to attend school or find work without his documented status. Now, he now faces deportation to a country he doesn’t know.

Kevin Vollmers — who works with Gazillion Strong, an advocacy group for marginalized people — is part of a group of activists seeking to pass an amendment to the Child Citizenship Act of 2000, which was Congress’ first attempt to address this issue. The 2000 Child Citizenship Act removed the requirement for parents of transnational adoptees to complete a lengthy naturalization process for adoptees: instead the Act established automatic citizenship for all children under the age of 18 born or legally adopted outside of the United States, and who are under the legal custody of a parent with US citizenship for two years within the U.S.

Unfortunately, the CCA applied an age restriction and didn’t include a grandfather clause. This means that adult adoptees like Adam — i.e. those who were born before 1983 — remain unprotected and undocumented. For the last three years, Vollmers and his colleagues have worked to try and amend the CCA to remove the age restrictions so that adoptees like Adam can receive protection.

It is currently estimated that over 300,000 transnational adoptees currently live in the United States; approximately one-third of those are Korean American adoptees. It is unknown how many adult Asian American adoptees are currently living without finalized naturalization paperwork; however, Asian American advocacy groups working on the broader issue of immigration reform note that over 1.3 million Asian Americans are undocumented in this country.

In 2013, the CCA amendment was applied to the Senate’s broad immigration bill and received overwhelming support from both the House and Senate. But, because the larger immigration bill failed to pass, the proposed CCA amendment is now an “orphan” amendment that has languished on the Hill without a new legislative sponsor.

Vollmers writes:

Honestly, it’s a travesty that we’re still having a conversation about adoptee citizenship and deportation. It’s an injustice that should have been addressed decades ago. Individuals like Adam were brought into the US by their adoptive parents. They were promised a better life here.

However, because adoptive parents forgot to finalize naturalization paperwork, people like Adam are at the risk of being deported, can’t get their drivers license, open bank accounts, etc. Adoptees have been deported back to countries for misdemeanor crimes, back to countries where they don’t know the language or have any support systems available to them.

It’s not just the adoptive parents who are at fault here, though. It’s the adoption agencies and the adoption lobby in DC who bear responsibility for turning a blind eye all of these years. And the adoption system itself bears responsibility for allowing this injustice to happen to the very individuals it supposedly helps.

Adam faces an April 2nd deportation hearing that will determine whether or not he will be able to stay in the only country he has ever known.

Poignantly, a commenter identifying as Adam writes in a comment to a blog post about transnational adoption: “all i know is american way of life.”

When did an American way of life come to mean deportation for survivors of childhood abuse like Adam, or survivors of domestic abuse like Nan-Hui Jo? (end)

Jenn Fang writes about issues affecting Asian Americans. Visit her website Reappropriate.co. (not com)