By Assunta Ng

Display reflects the building’s past (Photo by Assunta Ng/NWAW)

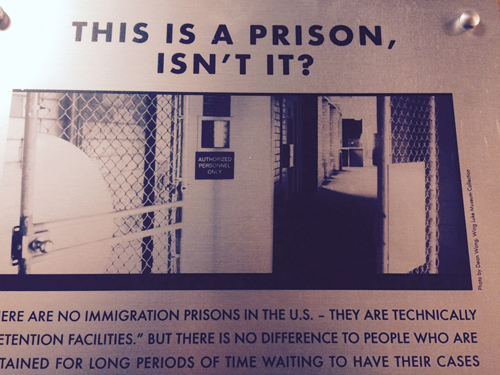

The Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) building is located in an auspicious corner of the Chinatown/International District. It has been transformed. The amount of history, injustice, suffering, and darkness hidden behind the building’s walls for the past seven decades would surprise visitors. But that has changed.

If you visit now, you will not sense the desperation of the past immigrant detainees inside the building. But you will still see the steel rods and the thick metal doors of the jail cells. The stern faces of the immigration judges who determined the fate of the thousands of illegal immigrants for over six decades have vanished, but the former swearing-in rooms now provide bright futures.

Louie Gong, Native American and Asian artist (Photo by Assunta Ng/NWAW)

I have spent hours waiting at the INS office as an international student getting and filing application forms for visa renewals, and later for my citizenship exam. The office was once an intimidating experience, as it must have been for many immigrants, even though we were not criminals. Why? We feared and perceived immigration officials as harsh, cold gods who controlled our destiny with no mercy.

However, the eyesore of the community is now a sanctuary for over 100 local artists. It has been transformed into working studios and exhibition spaces. The space has been renamed INSCAPE. There was an open house Sunday, December 7, and the Wing Luke Asian Museum hosted an exhibit of the Asian Pacific American Experience.

Elijah Evenson, scupltor (Photo by Assunta Ng/NWAW)

I have not been to the building for the past five years since its transformation. It was a surreal experience. Wandering on the first floor, I was greeted by smiling artists who took pride in their work in their studios, along with the other cheerful tenants of the building. The rent is reasonable: about $650 for over 350 square feet with the support of a city grant. You can’t get that kind of rent in any of Seattle’s prime locations any more. Each room has at least one, two, or three bright, tall big windows.

“I can work here 24 hours and nobody cares,” said one artist.

I met painters of all types, robot designers, sculptors, puppet makers, entrepreneurs, musicians, yoga instructors, and teachers. Many artists welcomed visitors with cookies, chips, candies, and one with pizzas. Of the 10 tenant artists I visited, only three were Asian Americans. I wish there were more.

What a difference compared to my visits in the 1990s, interviewing stowaways from China for the NW Asian Weekly. Each dingy, lonely cell has now changed to interesting works of art. The once desperate, anxious, and sad detainees are now replaced with talents, hopes, dreams, and energy. I couldn’t believe it. I pray that the painful chapter of the building will disappear forever. (end)