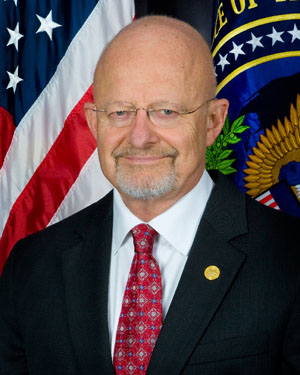

James Clapper

By Calvin Woodward

Associated Press

WASHINGTON (AP) — When U.S. spy chief James Clapper flew to North Korea on a mission to bring home two U.S. captives, he ran into a potential hitch. North Korean officials wanted a diplomatic concession of some sort in return for freeing the men and Clapper had none to offer.

“I think they were disappointed,” Clapper said, fleshing out details of the secret trip a week after its completion.

It was not until he was ushered into a hotel room for an “amnesty-granting ceremony” that he knew the release of Americans Kenneth Bae and Matthew Miller would proceed as planned.

All told, the trip unfolded more smoothly than his first foray into North Korean air space, aboard a U.S. helicopter in December 1985.

“They shot at us, and fortunately we made it back to the South,” he told CBS’s “Face the Nation” in an interview broadcast Sunday. At the time, Clapper was intelligence chief for U.S. forces in South Korea. This time, he was a presidential emissary with a deal in the works and permission to land.

Clapper arrived in Pyongyang in the dark, was taken to a guest house and met by a small party led by the state security minister and a translator. A “terse” dinner followed, hosted by the head of the Reconnaissance Guidance Bureau, which Clapper described as a combination intelligence unit and special operations force.

North Korea “feels itself to be under siege,” he said. “There is a certain institutional paranoia and that was certainly reflected in a lot of things that he said.” Clapper heard complaints about the U.S. interfering with North Korea’s internal matters. “It wasn’t exactly a pleasant dinner.”

He brought a short letter from President Barack Obama characterizing North Korea’s willingness to release the pair as a positive gesture. But the North Koreans wanted more.

“I think the major message from them was their disappointment that there wasn’t some offer or some big — again, the term they used was `breakthrough.”’

Afterward, Clapper waited hours until he got word that he had 20 minutes to pack his luggage for a drive to a downtown hotel. It was then he knew he would be leaving with Bae and Miller.

At a ceremony, Clapper exchanged handshakes with his North Korean interlocutor, the prisoners changed clothes and they left for the flight back.

The U.S. and North Korea have no formal diplomatic relations and a legacy of mutual hostility. Clapper sensed a “ray of optimism” about the future from his brief encounter with a younger generation — specifically, an official in his 40s who accompanied him to the airport and “professed interest in more dialogue, asked me if I’d be willing to come back to Pyongyang. Which I would.”

In any event, said Clapper, visiting North Korea has “always been on my professional bucket list.”

Bae was detained in 2012 while leading a tour group to a North Korean economic zone. Miller was jailed on espionage charges after he allegedly ripped up his tourist visa at Pyongyang’s airport in April and demanded asylum. They were the last two Americans held captive by North Korea. (end)