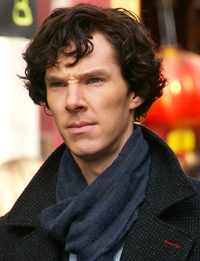

Benedict Cumberbatch

By Fu Ting

Associated Press

SHANGHAI (AP) – Zhou Yeling dragged herself out of bed at 5 a.m. for a long-awaited date with her favorite Englishman — Sherlock Holmes.

Zhou, 19, watched the third season premiere of the BBC’s “Sherlock” on Jan. 2 on the British broadcaster’s website. Two hours later, the episode started showing with Chinese subtitles on Youku.com, a video website.

Youku says it was viewed more than 5 million times in the first 24 hours, becoming the site’s most popular program to date.

“I was excited beyond words,” said Zhou, a student in the central Chinese city of Changsha.

“Sherlock” has become a global phenomenon, but nowhere more than in China, which was one of the first countries where the new season was shown.

Online fan clubs have attracted thousands of members. Chinese fans write their own stories about the modern version of author Arthur Conan Doyle’s prickly, Victorian detective and his sidekick, Dr. Watson, to fill the time between the brief, three-episode seasons. In Shanghai, an entrepreneur has opened a “Sherlock”-themed cafe.

Holmes is known in China as “Curly Fu,” after his Chinese name, Fuermosi, and star Benedict Cumberbatch’s floppy hair. Watson, played by Martin Freeman, is Huasheng, a name that sounds like “Peanut” in Mandarin. They have become two of the most popular terms in China’s vast social media world.

“The ‘Sherlock’ production team shoot something more like a movie, not just a TV drama,” said Yu Fei, a veteran writer of TV crime dramas for Chinese television.

Scenes in which Holmes spots clues in a suspect’s clothes or picks apart an alibi are so richly detailed that “it seems like a wasteful luxury,” Yu said.

Even the Communist Party newspaper People’s Daily is a fan.

“Tense plot, bizarre story, exquisite production, excellent performances,” it said of the third season’s premier episode.

With its mix of odd villains, eccentric aristocrats, and fashionable London settings, “Sherlock” can draw on a Chinese fondness for a storybook version of Britain.

“The whole drama has the rich scent of British culture and nobility,” Yu said. “Our drama doesn’t have that.”

Youku.com says that after two weeks, total viewership for the “Sherlock” third season premiere had risen to 14.5 million people. That compares with the 8 to 9 million people who the BBC says watch first-run episodes in Britain. The total in China is bumped up by viewers on pay TV service BesTV, which also has rights to the program.

Appearing online gives “Sherlock” an unusual edge over Chinese dramas. To support a fledgling industry, communist authorities have exempted video websites from most censorship and limits on showing foreign programming that apply to traditional TV stations. That allows outlets, such as Youku.com, to show series that might be deemed too violent or political for state TV and to release them faster.

“Our writers and producers face many restrictions and censorship. We cannot write about national security and high-level government departments,” Yu said.

Referring to Mycroft Holmes, a shadowy government official and key character, Yu said, “Sherlock’s brother could not appear in a police drama in China.”

Terigele, a 25-year-old geological engineer in the northern region of Inner Mongolia, started an online “Sherlock” fan club in 2010. The group has grown to become the biggest on the popular QQ social media service, with more than 1,000 members.

“I’ve watched several versions of Sherlock Holmes, and this is my favorite one,” said Terigele, who like many ethnic Mongols uses one name. “The fans in my group, and I too, think it is especially interesting to bring these two men into modern society, with the Internet and high technology.”

And Chinese fans have fallen in love with Cumberbatch.

“I am always super excited to see him on the screen and murmur, ‘Wow, so beautiful’ every single time,” said Zhang Jing, 24, who works for an advertising company in the eastern city of Tianjin.

That fondness for the performers has helped fuel a fad for “Sherlock” fan fiction in China. Some stories play on the complicated relationship of Holmes and Watson by making them a gay couple.

“The sexual orientation is also an interesting point,” Terigele said. “Their relationship is a bit more than friendship. They appreciate each other. It is cute, and it makes the audience more eager to watch it.”

And “Sherlock” makes a helpful cultural ambassador for Britain.

When Prime Minister David Cameron visited China last year, fans posted appeals on microblogs for him to press the BBC to speed up the release of a new season.

Today, a popular online comment aimed at Cameron is, “Thank you for ‘Sherlock.’” (end)