Wen Liu, contributor

contextChina.com

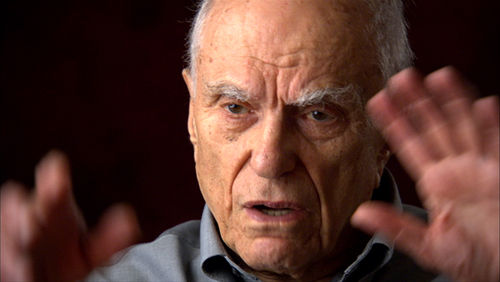

Sidney Rittenberg in the film, “The Revolutionary.” (Photo courtesy of Stourwater Pictures)

Sidney Rittenberg has played a remarkable role in U.S.-China relations since as far back as 1945, when he landed in Kunming as an American GI with Chinese language training. For the next 35 years, Rittenberg, now 92, lived in China through its civil war, the Cultural Revolution, and the beginning of the economic reforms. Watching today’s China under the new leadership of Xi Jinping, Rittenberg can draw on his friendship with Xi’s father, the late Xi Zhongxun, as well as decades of his first-hand experience living and working in the center of the China life, first in Yan’an, the communist revolutionary base, and later in Beijing, the capital.

With recent upheavals, from the Bo Xilai trial to an online crackdown to investigations targeting Western companies, contextChina asked Rittenberg to weigh in on the current political and economic situation. The following interview is Part 1 of a two-part Q&A, the first part focusing on politics and the second part on the economy and U.S.-China relations.

Mao Zedong signs Sidney Rittenberg’s copy of The Little Red Book during a gathering of party leaders in Beijing on May 1, 1967, at the beginning of China’s Cultural Revolution. (Photo courtesy of Sidney Rittenberg)

Q: Bo Xilai, the one-time flamboyant Party chief of Seattle’s sister city Chongqing, was sentenced to life imprisonment for bribery, embezzlement, and abuse of power. Would you say his case is an indication of China’s progress in the rule of law or a continuation of the same old power struggle?

A: To say power struggle is to obscure the fact that a struggle between different political programs underlies most such struggles, so they are not simply a matter of personal privilege. Political leaders require power in order to carry out their political program. Only the success of their program can ensure their maintenance of power.

Viewed in this light, I believe that Bo Xilai was taken down, not because his wife murdered an Englishman or because his chief henchman tried to defect, but because he was setting up a program and a power center that challenged Beijing’s program and ultimately its power. That is why, several years ago, when many were predicting a further rise in Bo’s career, I predicted (as quoted in the New York Times) that Bo would be taken down before he went any further. I had zero inside information, but I felt that anyone who jumped that high and yelled that loud was bound to pose a threat to Beijings policies and leadership, and would not be tolerated.

Actually, it is widely known that Bo’s crimes were much greater than what was dealt with in the court trial.

Rather than revealing a serious split in the CCP leadership, Bo’s sentencing shows that the leading circles reached consensus on how to deal with him and were therefore further united. Why was Bo first to fall, rather than other notoriously corrupt officials? For one thing, Bo took personal charge of both the criminal accumulation of personal wealth and the brutal persecution of anyone who got in his way — less prudent than other high-ranking criminals, in keeping with his swashbuckling, “no one can touch me” style.

Q: You were a friend of Xi Jinping’s father, the late Xi Zhongxun, one-time vice premier, as well as governor of Guangdong. What is your impression now of Xi Jinping, the first “princeling” president of China?

A: This is difficult to answer, because my impressions are based on observations at a distance. I believe, however, that Xi Jinping shows a strong sense of justice, as well as a genuine interest in Marxist principles something he has stressed continuously throughout his career. This is in sharp contrast to the mind-numbing repetitions of stock slogans to which we have become accustomed. Like his father, he tends to speak in his own voice and to understand that he should be a servant of the public, not its master. It is, of course, far too early to tell at this point, but I think that he is trying to inspirit the Chinese people, to sweep aside the political cynicism, to offer hope for the future. Also, he is working hard to consolidate his political support so that he can carry through the drastic economic reforms, which the CCP leadership decided were essential more than 10 years ago. Our personal experience with Xi (whom I have never met) is that he believes in dealing fairly with foreign investors.

Q: A recent Party document reportedly listed “seven erroneous ideological trends,” including Western constitutional democracy, universal values, and civil society. Why do you think the Party, when China is stronger than ever, still seems to feel threatened by Western ideas?

A: The CCP feels threatened by some Western political concepts because they challenge its rule in China. To reshape and rapidly expand a complex, huge, ancient, backward economy requires a great deal of cohesion and dedication this has paid off richly for the Chinese people, who have succeeded in lifting hundreds of millions out of pauperdom and transforming their lifestyle. Could this have been done with contesting political parties in control, with the divisions and clashes and deliberate stalemating from which we are suffering in America? Or in India? I seriously doubt it. The CCP wants to preserve this political cohesion and to preside over a lively, democratic society based on consultation and on training leaders in the Mass Linelistening to the demands of the people, and responding to them with appropriate policies. But squaring this circle is very difficult, especially in a country that lacks democratic traditions everyone knows that democracy means the majority decides. Very few understand that it also absolutely requires protecting the rights of the minority. Even during the student demonstrations of 1989, the student group in charge in Tiananmen Square tended to overwhelm various minority student groups.

A country like China has a definite potential for chaos and anarchy. The Cultural Revolution was a horrifying example of “mass democracy,” unrestrained by the state, wreaking havoc on a huge scale. There is great anxiety lest that sort of chaos should come again. Nevertheless, I think that this anxiety is overdone, and that the importance of democratization for stability is underestimated.

Q: In the last few months, we have seen an online crackdown, along with a new emphasis on the Party’s control of the media. Do you think there is a return to the Left or is it Xi Jinping’s way to consolidate power, as you said at a recent China Club dinner, to prepare for more reforms down the road?

A: It’s hard to say what’s “Left” and what’s “Right” in China today. We have all seen a swing towards the Right, stepping up controls over public expressions of opinion. Whatever the motivation, objectively this serves to consolidate Xi’s position among CCP leaders. Why? Because it establishes him as a trustworthy guardian of Party rule. As for more liberal members of the leadership, they have no choice but to support Xi anyway, so nothing is lost there. I suspect (but this is pure speculation) that as economic restructuring proceeds, we will see this tightening up of controls fade away, as was the case with Deng Xiaoping’s campaign against “bourgeois spiritual pollution.”

In fact, even during this tightening up period, we see moves in the opposite direction — like the setting up of a website with protection promised for all whistle-blowers who use it to expose corruption and wrongdoing. In the Chinese media today, one can criticize just about any government policy (like, the attitude towards North Korea, or the “stimulus” approach to economic issues), but you cannot challenge the absolute leadership of the CCP. In their view, the worst thing that could happen for China would be, in the ancient expression, “Tai E dao chi” — the hilt of the sword lands in someone else’s hands.”

Q: We can’t seem to go a week without hearing some big government official put under investigation for corruption. Xi Jinping talked about catching “tigers” and “flies,” or high and low level officials, alike. Wang Qishan, the new head of the Party central disciplinary commission, also seems very determined to do his job. Do you think the Party can really rid itself of corruption?

A: In the 1950s, after the great patriotic public health campaign, flies and mosquitoes were believed by many to have been wiped out in China. When a Japanese delegation visited and met with Chairman Mao, they congratulated him over the fact that, in all their travels, they had not seen a single fly. With his typical dry Hunanese wit, Mao responded, “Well, you didn’t look very hard!”

Similarly with corruption. As long as per capita wealth is so low, as accumulation of wealth is so unequal, as the distribution, marketing, and finance sectors of the economy are so irrational, there will always be corruption.

Xi’s aim is not to eliminate corruption, but to greatly increase the proportion of clean government and to revive among the young people the moral standards that used to typify “New China.” For all the tragedies of Mao’s day, at that time, there were little bank branches on many corners, the door was wide open, the cash was piled up on tables inside, there were no guards, and bank robberies were unknown. The problems in public morality involved submitting to Mao’s obsession with class struggle, not day-to-day relations among people.

The documentary, The Revolutionary, was the subject of an NW Asian Weekly article in May 2012.