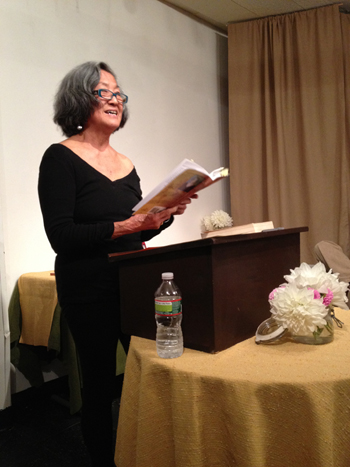

Nellie Wong (Photo courtesy of the Freedom Socialist Party)

By Signe Predmore

Northwest Asian Weekly

If there’s one thing that Oakland-based poet Nellie Wong wants to make clear, it’s that she’s no Amy Tan.

Wong, a bold poet, offers readers and listeners a window into her experience as a Chinese American woman. But she said her experience should be differentiated from Tan’s.

“[Tan is] a very fine writer, but her stories and novels speak about a certain part of China, in Shanghai, and about the upper class,” Wong told her audience. “That’s not us, that’s not our experience. What happened to the folks who lived and grew up on the land and were peasants and farmers in the USA?”

Wong hosted a reading of her work at New Freeway Hall in Columbia City, the local headquarters of the Freedom Socialist Party, on Dec. 1. She visited Seattle as part of a tour to promote her new book of poetry, “Breakfast Lunch Dinner,” which contains work written over a span of 40 years.

Many of the poems share her formative experiences, from growing up in her family’s Oakland Chinese restaurant “where my sisters and I labored without wage, but survived with tips and ngow ngook fahn, beef over rice,” to her training in the secretarial skills that supported her for much of her adult life, “as if learning to type without mistakes was a coveted prize that only girls with no hope of college could ever win.”

Wong proudly identifies as a feminist, a socialist, and a voice of the working class. She has been politically active for many years in Radical Women and the Freedom Socialists, who hosted her reading.

At a reception prior to the reading, guests were treated to a pan-Asian buffet organized through donations from several International District businesses and contributions from volunteers. Wong caught up with old colleagues and friends from her political organizing past.

Later, she shared selections from the new book, projecting confidence and humor as she read. Many of her poems are personal, such as “In the Blood,” in which she recounts how her parents were legally registered as brother and sister for many years after their arrival to the United States, due to a law at the time that prevented Chinese male immigrants from bringing wives. Other poems are inspired by global events, which Wong has only encountered in the newspaper. But all of her work is united by the common thread of political struggle.

After the reading, a discussion ensued on the challenges of being a political poet.

“When we were at State together, the big thing was, ‘Oh, that’s propaganda and if you write about politics, that can’t possibly be poetry,’” said Sukey Wolf, a former classmate of Wong’s at San Francisco State University. “Well, typically radical women, LGBTQ, all those underrepresented groups are … it’s not considered art to talk about our lives, which is the whole point of Nellie’s reading, you know?”

Wong said that fame and fortune were never her concerns. “My point is to get the work out, have people read it, enjoy it, like it, or give criticism or whatever it is, but it’s part of the community,” she said. “It’s for the radicals, and for the socialists, and for the feminists, and for the people of color, and the LGBTQ people, and all of us who are fighting to make change.”

Wong began writing in her mid-30s, taking night classes while working full-time as a secretary at Bethlehem Steel. Her younger sister Flo had watched her help their immigrant parents with English writing and typing tasks during their youth and thought she had a knack for it. Flo encouraged Nellie to give creative writing a try.

The Women’s Writers Union on the San Francisco State campus was the catalyst for Wong’s political awakening. She had written a poem criticizing the Chinatown Miss USA contest, and her professor responded, “Bitter, bitter, bitter. Once you have written a poem like that, you can throw it away.” When Wong shared this with the other feminist students in the union, and they told her, “Oh, you don’t have to listen to him!”

Early in her writing career, Wong performed and wrote as a member of Unbound Feet, an Asian American feminist literary group, until they broke up over political differences.

Wong found her voice as a poet and published her first book, “Dreams in Harrison Railroad Park,” in 1977. A few years later, in 1983, she was invited by writer Tillie Olsen to travel with the first U.S. Women Writer’s Tour to China, along with others, including Alice Walker and Paule Marshall. She was the only Chinese American woman to be included. At the very end of the tour, she managed to arrange a visit to her father’s village in Toisan, where she met her extended family. Her visit inspired a poem, “In China,” in which Wong writes about her desire to be “embrace[d], a daughter returning.”

In 2010, students from Oakland High School, Wong’s alma mater, voted to name a campus building after her.

In addition to the reading, Wong’s stay in Seattle included a brief poetry workshop with students at Ida B. Wells High School on the UW campus, and a rally in solidarity with dissidents in Russia and the Russian consulate.

In her 70s now, Wong is full of hope for the future. She is considering writing both a novel and a memoir and would like to write about connections between women in China and Chinese American women today.

When contemplating her next work, Wong reflects, “What is it about the things that happen to women and working people and poor people that I care about, that I could write about and help to put out there?” She feels there is much still to do. “If [people] think this is a post-feminist society, they’re crazy.” (end)

Signe Predmore can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.