By Steve Kadel

The Associated Press viA Times-News

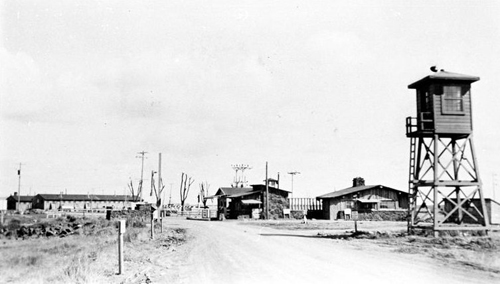

Front entrace of Minidoka relocation camp (Photo from preservationnation.com)

EDEN, Idaho (AP) — Monica Chin looked across the high desert land that used to be the Minidoka Relocation Center and shook her head.

“Did I go through all this?” she wondered aloud.

Seventy years ago, Chin lived inside the barbed wire compound about 15 miles northeast of Twin Falls. She was a bewildered 14-year-old girl who was incarcerated with thousands of other Japanese Americans during World War II.

Chin and dozens of others with personal memories of the internment camp visited the site Saturday during the annual pilgrimage. She said it wasn’t a bad feeling to be back, although it took years to make peace in her mind.

“For a long time, I didn’t want to talk about it,” Chin said. “There was all that time wasted and all the (financial) loss.”

The New Castle, Wash. resident expressed happiness that her children from Seattle and California could be on hand Saturday to learn about their family’s past.

The Minidoka camp, one of 10 such facilities in the United States, housed from 9,500 to 9,800 people at any given time, according to Anna Tamura of the National Park Service, who led a group through the grounds that now comprise the Minidoka Internment National Monument.

The camp operated from 1942 until November 1945.

Dennis Creed’s wife, Brenda, was born there in 1944.

“It wasn’t fair, but it is nice they’re bringing this to light, so it never happens again,” he said.

Although a couple of barracks and a building that served as a fire station remain, most of the camp has long been dismantled.

“I feel lost because there are no landmarks,” said Tokuko Murdoch of Arlington, Texas, another former camp resident.

She was a child during the war, and recalled playing with friends. Murdoch didn’t consider the camp a tremendous hardship at the time, she said, although not every aspect was pleasant.

“The only thing I didn’t like was having to eat when they told you to,” she said, adding that nighttime trips to a bathroom in a laundry building weren’t fun, especially when snow covered the ground.

“Some people deny it ever happened,” Murdoch said.

John Okazaki of Los Angeles was in camp as a 14- and 15-year-old boy. He went to high school during the morning and worked as a laborer in the afternoon and on weekends, earning $8 a month.

Like some others, who lived in the camp as children, he said he was too young to realize what was being taken from him.

“Everybody looked alike and you ran around with your friends,” he said. (end)

Information from The Times-News, www.magicvalley.com.