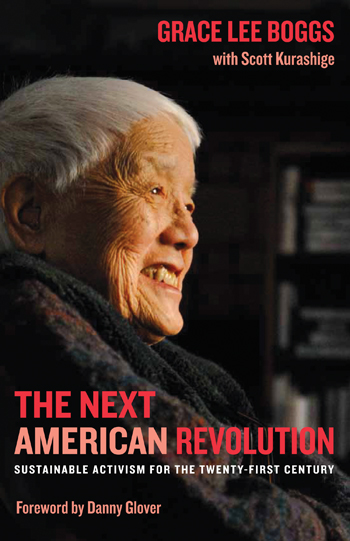

Cover of Grace Lee Boggs’ new book "The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century"

By Tiffany Ran

Northwest Asian Weekly

Longtime activist Grace Lee Boggs was asked to make the closing statement at the Asian American Reality conference at Pace University in the 1970s.

“This was the first time that I was asked to make a speech in my 40 years of being an activist,” said Boggs.

When she was young, she scoured the library for novels on Chinese culture, finding the rare few, like Pearl S. Buck’s “The Good Earth.”

Decades later, Boggs stood before a crowd of Asian Americans at Pace University bearing witness to signs of a newly emerged Asian American movement.

Approaching imagination

Boggs’ father emigrated from Taishan, China, and got his start in Seattle in 1911 before moving to Providence, R.I. Boggs was born in the apartment above her father’s restaurant.

“I was born in 1915 in what was later known as the First World War, two years before the Russian Revolution, and because I was born to Chinese immigrant parents and because I was born a female, I learned very quickly that the world needed changing,” said Boggs.

“But what I also learned as I grew older was [that] how we see the world and how we change the world have to change.”

In the early 1930s, at age 16, Boggs witnessed the Great Depression from behind college gates as a student at Barnard College. She watched as fellow students joined the Communist Party and took part in protests. She felt the need to turn inward to question the riotous world around her. When she graduated in 1935, many stores and businesses still refused to hire “Orientals.”

Instead, Boggs enrolled at Bryn Mar College to earn a doctorate in philosophy. Throughout her time in school, Boggs felt the need to experience grassroots issues and organizing at ground level. While her protests began as silent and internal, that would soon change, as would she.

She recalls an incident when she boarded a train from Ohio to New York. Once the train crossed the Ohio River, a demarcation of the Mason Dixon line, a train conductor approached her and asked her to move from her regular coach seat to the Jim Crow car with the other Black passengers. He later found her in her new seat, saying he was mistaken, and told her she could return. But instead, Boggs remained in the back with the other Black passengers.

Around this time, Albert Einstein gave the famous line that Boggs often referred to in later years.

“The splitting of the atom has changed everything but the human mind, and thus we drift towards catastrophe.”

“He also said that ‘imagination is more important than education,’ ” said Boggs.

In 1941, Boggs took part in the March on Washington Movement led by A. Phillip Randolph.

Randolph’s words inspired Boggs to join the radical movement. Her work led her to Detroit in the early 1950s, where she authored “the Correspondence” newsletter along with influential theorist C.L.R. James. She married Black auto worker and activist James Boggs.

“I felt really comfortable being involved in the Black movement. I started getting involved in the Black movement because it began by addressing workers’ rights,” said Boggs.

Boggs participated in the Workers Party’s South Side Tenant’s struggle against rat infested housing in the neighborhood and learned more about segregation and oppression in the Black community.

She experienced these struggles first-hand once she married, finding that she was pulled over by the police more often when her husband was in the car. And when he moved into her apartment, the couple was evicted. The couple was also denied hotel rooms during their travels. Their combined experiences — Bogg’s intellectual perspective joined with her husband’s contrasting rural factory worker background — made the two a dynamic couple in the Black movement and local community organizing.

Afro-Chinese

Though she flourished as an activist in the Black community and was welcomed as a member of her husband’s family, she grew distant from her own family, from which she had lived apart for many years. With the exception of one brother who worked with her on “the Correspondence,” Bogg’s work fell on blind eyes when it came to most of her family members.

“By the time that I became active in activism and social organizing, I’d already lived away from my parents for quite a long time, so there wasn’t any direct disapproval,” said Boggs.

“My father, like other immigrants around that time, was a supporter of the Chinese Revolution of 1911, so the idea of revolution and protest was not foreign to him. [But] if anything, he was apathetic about what I did.”

When her father visited Boggs and her husband, she was surprised by how close her father seemed to be with her husband. However, a divide grew between Boggs and her mother. It would be an estrangement that would last for 16 years. She was never quite able to explain the cause of their drift, but suspected that it had to do with the nature of her work and the color of her husband’s skin.

One day, her estranged brother asked to meet with her and, to her surprise, he appeared as a U.S. Military Intelligence service officer and interrogated her on her radical activities. He showed that he had access to her FBI files, which described her as Afro-Chinese, instead of just Chinese.

“I don’t think young Asian Americans on the West Coast understand how invisible Asians were back then. The Asian American movement didn’t really start until the late 1960s and also with Vincent Chin’s murder. By the time that happened, I had already been an activist for a long time,” said Boggs.

In 1968, an incident at the Detroit Airport reminded Boggs of the differences between her and her husband. When returning from a trip, her husband breezed through customs, while Boggs was subjected to close scrutiny by officials who, by looking at her, suspected she could be an Asian drug smuggler. In Detroit, Grace co-founded the Asian Pacific Alliance. With only a handful of members, Boggs organized anti-Vietnam War protests and began learning more specifically about Asian marginalization.

Next American Revolution

At the age of 96, having witnessed nearly a century’s worth of political and social change, Boggs credits her desire to keep afloat in an ocean of change to maintaining the right mindset.

“Asian Americans should be careful not to adopt a victim or minority mindset,” said Boggs.

While her identity as an activist evolved, her belief in philosophy was never far behind. She identifies as a philosophical activist, one that couples acting for change with reimagining the idea of change.

“The time has come for us to reimagine everything,” said Boggs, in reference to Einstein’s words.

“We have to reimagine work and get away from labor. We have to reimagine revolution and get away from protest. We have to reimagine institutions and think about our own internal change.”

In 1992, she co-founded Detroit Summers, a multi-racial and multi-generational collective approach, through youth leadership, music, poetry, and art to address community — as part of the solution.

In recent speaking engagements earlier this month, Boggs defined the “Next American Revolution,” also the title of her new book, as one in which activists take part in reimagining new solutions for their community, rather than just protesting ways in which government and corporations have erred, expecting them to fix it.

On the day after her talks, Boggs was surprised with a large celebration in her honor, where the San Francisco Board of Superiors proclaimed March 3, 2012 as Grace Lee Boggs Day in San Francisco.

“I was surprised by all the hard work that Pam Tau Lee (founder of the Chinese Progressive Association) and the young activists put into the music, promotion, and performances,” said Boggs.

When asked how she would prefer others to celebrate her holiday, Boggs replied simply that celebrating with the community amidst art, diversity, and music is a valuable aspect of activism, and she was pleased to be a source of that. (end)

Tiffany Ran can be reached at tiffany@nwasianweekly.com.