By Kate Brumback

The Associated Press

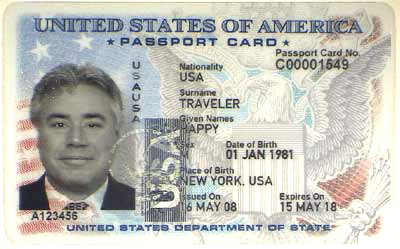

An example of a wallet-sized passport card

BAYOU LA BATRE, Ala. (AP) — Alabama’s tough new law targeting illegal immigrants has provoked concern among Latinos — even causing some to leave the state — but members of other immigrant groups appear to be less worried.

Mai Nguyen, a Vietnamese refugee who arrived more than 20 years ago in Bayou La Batre, the heart of Alabama’s Gulf Coast seafood industry, said there was some initial fear, especially among those who speak limited English.

“I was a little worried when I first heard about it because I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to explain to a police officer that I’m here legally,” Nguyen said through a translator. But now, she says she’s more concerned about the shrimp harvest.

Nguyen is part of the robust community of Southeast Asians who settled here after the Vietnam War. Since they are naturalized American citizens or legal permanent residents, Alabama’s new law targeting illegal immigration shouldn’t affect them.

Some parts of the law have been blocked by courts, but a section that allows police to check a person’s immigration status during traffic stops still stands. Some immigrants, even those in the country legally, worry that this could lead to improper detentions or racial profiling — concerns that police and supporters of the law dismiss.

People in Bayou La Batre’s Southeast Asian community, especially the older generations, have been encouraged to apply for wallet-size passport cards that they can easily keep with them. That helped alleviate fears about the law, said Grace Scire, regional director for the Vietnamese American advocacy group Boat People SOS.

Since Alabama’s law was enacted, many Latinos — the state’s fastest growing immigrant group over the last decade — have reportedly left the state. Even among legal residents, many said they were leaving either because they feared the law would lead to racial profiling or because they have family members who are here illegally.

“Hispanic immigrants definitely feel like this is a law targeting Hispanics,” said Elizabeth Brezovich, with the Alabama Coalition for Immigrant Justice. But she added that some other immigrant groups are worried.

“It’s making a lot of people start to think — even if they’re here legally — about what they need to do to get their papers in order, to make sure they’re OK if they get stopped by police,” she said.

“The legislative hearings and record bear out that the people who introduced and passed the law were motivated to get Hispanics to self deport,” said Olivia Turner, with the American Civil Liberties Union of Alabama. “But I think its effects may be broader.”

Turner said she’s heard from members of the south Asian community, many of whom are Muslim, that this law is yet another tool that will be used to harass them in the aftermath of 9/11. Some Haitian immigrants fear it will lead to racial profiling, she said.

Nguyen arrived in Bayou La Batre in 1990 after spending a year in nearby Mobile. She can see some parallels between her own experience and that of the Latinos.

When she first arrived with her family, seeking a better life, some American workers resented the foreigners filling jobs — even humble jobs like shucking oysters. One of the main stated purposes for Alabama’s new law is to make sure illegal immigrants don’t take jobs from Americans.

As refugees, including many who fled persecution after communist regimes seized power, the Southeast Asians have legal residency status and many are naturalized American citizens.

They’ve lived in Bayou La Batre for more than three decades and are entrenched in the local economy.

Nguyen sympathizes with the Hispanic immigrants somewhat, but she said the law might have a good effect if illegal immigrants leave the state. They are often willing to work for lower wages and in worse conditions, meaning employers tend to prefer them over those who are here legally, she said.

And with boats staying docked amid a slow economy, lots of people need jobs.

Food market owner Tom Khanthavongsa and his wife, Duang, immigrated to the United States from Laos in 1980. Khanthavongsa, 55, said he hasn’t given much thought to the new law.

“We’re not worried, we have all our papers and everything,” he said, adding that a bigger concern is the struggles of the local Southeast Asian community who are his primary clients.

Across Mobile Bay, along the Gulf Coast, which attracts hordes of tourists to its white sand beaches in the summer, many low-skilled jobs are filled by workers from other countries.

Employers in Gulf Shores and Orange Beach, where beachfront hotels, souvenir shops, and waterfront restaurants cater to tourists, said they lost some Hispanic workers — who they say were here legally — when the law took effect.

But many jobs are filled by young people from Eastern Europe or Jamaica who come on temporary work visas to wait tables or clean hotel rooms during the summer high season. The law took effect as the season was ending, so it’s too early to tell whether it will dampen their willingness to come to Alabama.

Eugeniu Gorbatia works as a bartender in a harbor-side restaurant. The 28-year-old from Moldova, who was granted political asylum, has lived in the United States for five years and speaks with a thick accent. He said he’s not worried about the new law.

“I was pulled over during the summer, but the police didn’t ask me about my immigrant status,” he said. “But if they did, I wouldn’t worry. I have my papers.”

His employer, Matt Shipp, said his workers on temporary seasonal visas weren’t concerned about the new law, but he lost a handful of Hispanic workers, all of whom he believes are in the country legally. Some moved to Florida where the laws are less strict.

In the Montgomery area, the small Korean population is only concerned that the broad discretion granted to police officers may be misused, said Alabama State University professor Sun Gi Chun.

“Most people [in the community] are working here legally, so we don’t have any fear about the law,” he said. “We are a little concerned about people who might abuse their authority, but we haven’t felt any abuse so far.”

Mohamed Elhady, president of the Huntsville Islamic Center, which has members from many places, including India, Pakistan, Turkey, and the Middle East, said he hasn’t heard much concern about the new law.

“Our community is different,” he said. “It is made up of professionals — doctors, teachers, engineers — who are all here legally, so the law doesn’t affect us. We are not concerned.” (end)