Liu Xiaobo

By Gillian Wong

The Associated Press

BEIJING (AP) — In a quiet, leafy neighborhood of Beijing, a woman has been living in enforced isolation in her book-lined, fifth-floor apartment. Her apparent misdeed: being married to a Nobel Peace Prize winner the Chinese government calls a criminal.

In the year since jailed democracy campaigner Liu Xiaobo was awarded the prize, his wife Liu Xia has also become a prisoner. She has largely been held incommunicado, effectively under house arrest, watched by police, without phone or Internet access and prohibited from seeing all but a few family members.

“Liu Xia has been completely cut off from communication with the outside world, and leads a lonely and oppressed life,” said Beijing activist Zeng Jinyan, the wife of another well-known dissident who has endured bouts of surveillance and harassment. “It has already been a year, I dare not imagine how much longer she must bear this pain.”

The Nobel prize announced last Oct. 8 cheered China’s fractured, persecuted dissident community and brought calls from the United States, Germany, and others for Liu’s release, but also infuriated Beijing, and authorities harassed and detained dozens of his supporters in the weeks that followed.

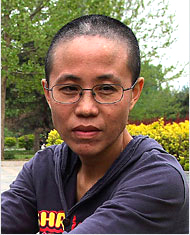

China has a long history of punishing family members of government critics. But the Liu case is different because he’s the first to win the Peace Prize and by isolating Liu Xia, the government seems intent on preventing the frail-looking 51-year-old poet with close-cropped hair and wire-rimmed glasses from becoming a rallying point for political activists.

“The Chinese government simply just does not want people to be reminded of the emotional, the human aspect of Liu Xiaobo in jail, and to do that, they also want to erase Liu Xia from people’s memory,” said Wang Songlian, a researcher with China Human Rights Defenders in Hong Kong.

The harsh treatment of Liu Xia seemingly runs afoul of China’s laws and might be the most severe retaliation ever suffered by the family of a Peace Prize laureate.

“As far as I know, the way she is treated is unprecedented in the history of the Nobel Peace Prize,” said Geir Lundestad, secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. “Her situation is extremely regrettable.”

Lundestad said the committee is also worried about Liu Xiaobo because it has not received any new information about his situation since late last year.

The government did not comment.

A literary critic and dogged campaigner for peaceful political change, Liu Xiaobo tried to negotiate the retreat of pro-democracy student demonstrators from Tiananmen Square in 1989. He co-authored a manifesto in 2008 calling for an end to single-party rule. Both acts earned him jail terms, the latter an 11-year sentence he is now serving.

Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia’s friendship began in the early 1980s over a shared love of literature and poetry. Her father, a senior finance official, had set up a cushy job at the national tax bureau for her, but she quit because she wanted more freedom, according to an essay about the couple by dissident writer and friend, Yu Jie.

They wedded in 1996 while he was in a labor re-education camp in order for Liu Xia to be granted permission to visit him. Yu’s essay says she told police, “I just want to marry that ‘enemy of the state!’ ”

In a tribute to Liu Xia, Liu Xiaobo wrote, “I am serving my sentence in a tangible prison, while you wait in the intangible prison of the heart,” as part of a statement he had prepared for his trial in 2009.

Two days after the Nobel announcement, which brought furious condemnation from Beijing, Liu Xia was allowed to visit him in prison. She carried out a message from him that he dedicated the award to those who died in the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown. Rights groups say she hasn’t been allowed to see him since.

During a rare phone interview with the AP a few days after the award was announced, Liu Xia sounded hopeful her confinement would be brief. “I’m sure that for a moment, the pressure will be greater, I will have even less freedom, even more inconvenience, but I believe they won’t go on like this forever and that there will be positive change in the future.”

On a recent day, there were no signs of movement in her apartment that could be seen from the ground floor, although a window was open and a light in a small room was switched on at night. Downstairs, residents walked their dogs near a river where Chinese men were swimming and fishing.

Liu Xiaobo was not allowed to attend the funeral of his father last month and it’s not clear that he or Liu Xia know that he died Sept. 12, because his brother could not reach him, said Liu Xiaobo’s close friend, Wu Wei. Wu said he was informed by Liu Xiaoxuan, Liu Xiaobo’s younger brother, who told the AP he was not allowed to accept foreign media interviews.

“He said there was no channel, no way to inform Xiaobo and Liu Xia, so that means that they do not necessarily know the news,” Wu said in a phone interview.

Despite being more beleaguered since the Nobel prize, many of China’s dissidents say they cherish the recognition.

“Awarding Liu Xiaobo the prize had the overall effect of helping to energize China’s civil opposition and rights defense movement,” said Wu, the writer. “Just like South Africa had their Mandela and Myanmar had their Aung San Suu Kyi, we now have Liu Xiaobo.” (end)

Associated Press writer Bjoern Amland contributed to this report from Oslo, Norway.

Follow Gillian Wong on Twitter at twitter.com/gillianwong.