By Andrew Hamlin

Northwest Asian Weekly

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Khmer Rouge, Cambodia’s ruling party from 1975 to 1979, killed more than 1.3 million Cambodian citizens, according to an analysis by Yale University. Factor in the widespread disease and starvation during those times, and the death toll under the Khmer Rouge rises to somewhere between 1.7 and 2.5 million, according to the UK’s Peace Pledge Union.

The Khmer Rouge, Cambodia’s ruling party from 1975 to 1979, killed more than 1.3 million Cambodian citizens, according to an analysis by Yale University. Factor in the widespread disease and starvation during those times, and the death toll under the Khmer Rouge rises to somewhere between 1.7 and 2.5 million, according to the UK’s Peace Pledge Union.

Many victims died in what Cambodian journalist Dith Pran called the “killing fields,” sites where state-sanctioned killers tossed bodies by the score into mass graves.

The Khmer Rouge, lead by Pol Pot, targeted non-Cambodians, intellectuals, Muslims, Christians, Buddhists, and anyone who spoke out against the Khmer Rouge.

After being toppled by Vietnamese forces in 1979, Pol Pot spent the rest of his life in a remote Cambodian residence near the Thailand border. He died mysteriously in 1998, just a few hours after the Khmer Rouge’s Ta Mok faction declared that they would turn him over to an international tribunal.

Pol Pot never took responsibility for the killing fields. No high-ranking Khmer Rouge party member has ever spoken with a journalist, for the record, about the genocide.

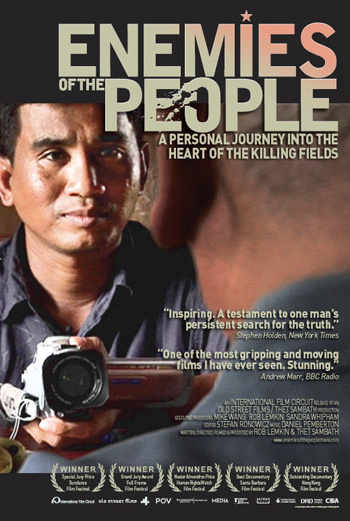

That is until now. “Enemies of the People” is a documentary on Cambodia’s killing fields.

The old man onscreen doesn’t have much hair left. The left side of his mouth lacks upper front teeth and twists into a half-snarl, leaving his face divided against itself.

He sits behind a simple table. A circular can of Cambodian potato chips, similar to American Pringles, sits by his right hand. A much younger man sits at the other end of the table, fiddling with a video camera.

The younger man is Cambodian journalist Thet Sambath, a reporter for the “Phnom Penh Post.” The older man is Nuon Chea, second-in-command for the Khmer Rouge. Pol Pot called himself “Brother Number One” to the Cambodian people. Nuon Chea was “Brother Number Two.”

Sambath explains that he’s been meeting with “Brother Number Two” since 2001. Every weekend, he travels several hours with his video camera, from Phnom Penh to Nuon Chea’s dwelling, not far from Pol Pot’s old house.

As the movie begins, Sambath explains that his father was killed by the Khmer Rouge and his mother died during childbirth after a forced marriage to a party member. He has not told Nuon Chea these things. However, he admits that the time to tell is coming soon.

Sambath, aided by his co-director Rob Lemkin, wants Nuon Chea to explain and to apologize. But the filmmakers don’t confine their research to “Brother Number Two.” They locate and interview two men who actually killed their own fellow citizens, and then dumped the bodies.

The men certainly don’t look evil. They look like ordinary middle-aged Cambodian men, although at times, Sambath’s close-ups catch a certain nervousness in their eyes. Their explanations of what they did seem straightforward enough. At times, they even seem apologetic.

Near the very end of the documentary, under a rainy sky, with bamboo torches burning around them, the men discuss intimate details of what they did. As thunder crashes around their words, the field insects crawling up their work shirts seem to possess a truer sense of purpose and morality.

As for the final confrontation between Sambath and Chea, I’ll leave that for you to see. This film can be very hard to watch. But it remains a film that everybody should watch. ♦

“Enemies of the People” plays Jan. 21–Jan. 27 at the Northwest Film Forum, 1515 12th Avenue in Seattle. For show times, prices, and directions, call 206.829.7863 or visit http://www.nwfilmforum.org/live/page/calendar/1605.

Andrew Hamlin can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.