By Amy Phan

Northwest Asian Weekly

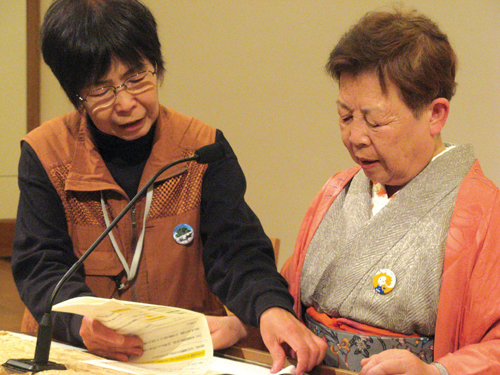

Tokie Mizuno (right) recounts the day Hiroshima was bombed in a nuclear disarmament presentation through the help of a translator in Seattle on May 5. (Photo by Amy Phan/NWAW) |

Tokie Mizuno said she was 5 years old when “Little Boy,” one of two atomic bombs used in warfare history, dropped.

She was at her grandmother’s house, less than a mile from the epicenter. Now 70 years old, she remembers that moment well.

“We were about to eat our sweets when the bomb exploded. With a blinding flash, the whole house was flattened,” Mizuno recounted through a translator at a nuclear disarmament presentation held in Seattle on May 5.

Immediately after the explosion, she said, she began searching for her family.

“I saw my mother crawling to me over piles of rubble; she looked awful with tatter patches of clothing on her body.”

Mizuno’s memory of Aug. 6, 1945, the day 30 percent — roughly 60,000 people — of Hiroshima’s population died, is scattered. Mizuno’s memories are aided by her parents’ and grandparents’ accounts.

“My right arm was heavily injured, and I had several cuts on my face.

My neighbor tore her underwear into pieces and covered my arm to stop it from bleeding,” she said.

She later learned that it was her neighbor’s actions that saved her right arm.

But even though her right arm was spared, the atomic bomb forever changed her life.

“I remember when I was in school, I knew the answers to the questions, but I just sat in my chair because I didn’t want to raise my hand [exposing the scar],” said Mizuno.

Three days after Hiroshima was bombed, the United States followed with “Fat Man,” the second atomic bomb, which immediately killed at least 60,000 people, by lower estimates.

And for the hundreds of thousands of civilians not immediately killed by the upwards of 7,000-degree Fahrenheit heat generated by the atomic bombs, numerous health and mental problems ensued.

Mizuno’s parents died 20 years after the atomic bomb, both deaths she believes due to long-term radiation.

Bombing victims became Hibakusha — a Japanese term literally translated into “explosion-affected people.”

Donald Hellman, University of Washington (UW) professor of international studies, said Mizuno’s memory of concealment was a common feeling for atomic bomb survivors.

“Vicitims [of the atomic bomb] were psychologically hung out to dry. There wasn’t a sympathetic embrace for the victims; people were ambiguous,” said Hellman, whose research work includes Japanese political economy and international relations.

In the 66 years since the atomic bombings, Japanese sympathy toward Hibakushas has changed drastically, said Hellman.

“There’s a real desire now to feel what it was like to be there when the bombs dropped,” he said. “Hiroshima and Nagaski were a big issue. … There’s this topic of ‘never again’ institutionalized around the atomic bomb,” he said.

This is how Mizuno came to understand her ‘explosion affect’-ion as well.

As her physical wound healed, time allowed Mizuno to develop the courage to share her experiences.

“I never thought that I’d talk about my experiences [of Hiroshima] to others. But I now understand it’s my duty to share my experiences with others because a nuclear weapon is inhuman and holding nuclear weapons is a criminal act against human beings,” she said.

The issue of nuclear disarmament trails closely at the heels of a month-long United Nations conference to review the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

Created in 1970, the main goal of the NPT is to limit the spread of nuclear weapons. The treaty currently has 189 signatories.

Among other countries, India, Pakistan, and Israel have never signed the NPT. North Korea ratified the treaty in 1985, then withdrew entirely from the NPT in 2003.

The effects of a nuclear bomb are spectacular.

An atomic bomb works by nuclear fission, a process that splits atoms indefinitely in a matter of seconds, ignited through high temperature and pressure.

There are a number of different types of bombs, however, the impact is essentially the same. When an atomic bomb diffuses, it releases tremendous amounts of energy that results in a blast wave and heat, as well as immediate and long-term radiation.

“It would take only seven or eight nuclear weapons to flatten Japan. It would take only 20 minutes, and it would all be over,” said Hellman.

With such powerful potential, the arguments for and against nuclear weapon possession and usage are heated.

Nuclear disarmament advocates, like Mizuno, point to the immoral ramifications of nuclear weaponry.

“Nuclear weapons are unspeakable weapons. They don’t allow us to live or die as humans. They are weapons of absolute evil,” she said.

But as the majority of the world has pledged nuclear non-proliferation, the few countries who openly possess nuclear weaponry hold a powerful negotiation tool: the military strategy of deterrence, which is a defensive strategy that governments employ to deter aggressors by promise of immense retaliation.

The more countries signed on to the NPT, the more a coveted position is created for the few countries actively pursuing nuclear weaponry because, although internationally unsupported, these countries possess unique military weapons that could, hypothetically, destroy entire countries much quicker than regular military artillery.

Clark Sorensen, UW chairman of Korean Studies, said current diplomatic efforts of the United States to disarm non-signatories of the NPT have reached a stalemate — most of which is due to slow negotiating talks.

Under the NPT, five countries are recognized nuclear weapon states: United States, Russia, United Kingdom, France, and China. These five countries are internationally recognized and authorized to have nuclear weapons, the treaty only encouraging the five countries to eventually reduce and eliminate their nuclear weapons.

In the case of North Korea, said Sorensen, the government is looking at the open nuclear development of India and Pakistan as an example of ‘why not?’

“North Korea has an ideology of self-efficiency. They want to be a normal country that is allowed to have military artillery,” Sorensen said. “North Korea thinks that India and Pakistan are both nuclear powers.

[They have] exploded nuclear weapons, and nothing has ever happened to them.”The nuclear division between the have and have-nots has caused debate on the local scene as well.

Presentation attendee Marion Watana thought about how the United States should protect itself in the threat of nuclear warfare. “As long as other countries have [nuclear weapons], we should be prepared as well,” said the Seattle resident.

It’s an argument Mizuno hopes to disarm.

“I’m always encouraged by supporters. More and more people want to understand Hiroshima and Nagasaki. People need to understand what nuclear weapons can do so we can abolish them,” she said.

Seventy-five percent of Japan’s population was born after the atomic bombings. Most of the Japanese population is no longer directly affected by that history.

“The young people in Japan are apolitical — they are not interested in nuclear disarmament. The national peace badge of Japan is pushed by the middle and older groups affected by the bomb,” said Hellman.

Which was why main organizer of the Seattle nuclear disarmament presentation, Leonard Eiger, wanted the Japanese delegation to speak in the Pacific Northwest.

“I wanted to put a face on this issue, since Japan is the only nation to have suffered the effects of the use [in war] of nuclear weapons. I feel that this is an important time to engage more people … by making them aware of the issues, educating them, and hopefully, motivating them to get involved,” he said.

He added, “So long as nuclear weapons exist, no matter how stringent and sophisticated the safeguards, there is some [albeit small] probability of detonation somewhere, sometime.” ♦

Amy Phan can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.