By Andrew Hamlin

Northwest Asian Weekly

Before leaving his home in Texas for Mongolia with his wife and autistic son, author and horse trainer Rupert Isaacson seems eager for the trip as he calls it a “gateway to adventure, a gateway to healing.”

Before leaving his home in Texas for Mongolia with his wife and autistic son, author and horse trainer Rupert Isaacson seems eager for the trip as he calls it a “gateway to adventure, a gateway to healing.”

The viewer will have to decide whether healing actually takes place in this documentary. The adventure, however, is right in front of our eyes.

Isaacson and his wife, psychology professor Kristen Neff, seek help for their son Rowan. Usually flailing, screaming, and unresponsive, Rowan becomes calmer when he’s around animals. Animals seem to sense his uniqueness and bond with him.

Isaacson also believes that the shamanic healers of Mongolia can help his son. Some of the most respected Mongolian healers herd and ride reindeers. Isaacson feels that Rowan can get benefits from both healers and reindeers.

Isaacson produced and narrated the “Horse Boy.” He also wrote the bestselling book based on the plot. The family received an advance of more than $1 million for the book rights to the story.

Isaacson hired filmmaker Michel Orion Scott. Scott often seems to be taking orders directly from Isaacson. However, with the camera, he studies the family intently and not always sympathetically.

Traveling with Rowan is never easy. Even with the animals around him, the little boy often screams for hours at a time. He has never been successfully toilet-trained. Whether you believe in the healing aspects of the film or not, your heart goes out to Rowan’s parents for what they endure every day.

Isaacson sometimes trips over his own ego. He tells us of the research he had done in preparation for the trip. But he seems confused when the family lands in Mongolia’s capital, Ulan Bator.

He wasn’t expecting what he later calls a “depressed post-Soviet city … this urban slum.” One wonders how thorough his research really was.

Kristen Neff doesn’t seem nearly as excited as her husband. In fact, she often seems weary and fearful on camera. “I don’t really believe in spirits,” she confesses at one point.

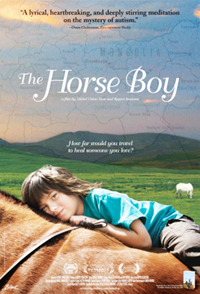

Screen shot from the film, “The Horse Boy,” of Rupert Isaacson and son Rowan (Photos provided by www.horseboymovie.com)

When Isaacson eats local Mongolian cuisine, he mutters his disgust over the food.

He has to rely on the translator he hired for the trip to communicate with natives. The translator’s son becomes friends with Rowan. This warm cross-cultural friendship could have become a film in its own right.

Unfortunately, the boy never gets asked what he thinks about Rowan.

Words from the healers themselves might have also helped. We hear about the magic they profess, but wo don’t hear much about who they are or how they operate when the cameras aren’t on them. They seem to simply appear, hover around Rowan, and then disappear again.

No one can say for sure if Rowan comes out of the experience for the better. Back at home, he seems calmer, more rational, and interacting more with other children. Isaacson seems satisfied that his son’s behavior improved due to the experience.

It is important to note that the evidence presented is not conclusive. The beneficial effects of any mystical or spiritual healing have never been concretely established by using scientific methods. Many scientists remain skeptical. Some autism experts interviewed in the film agreed that autistic children can go through phases of improved behavior for no identifiable reason.

Was the long, grueling, and laborious trip worth it? Isaacson thinks so. In a film with so many uncertainties, the final verdict is ultimately up to the viewer. ♦

“The Horse Boy” opens Friday, Nov. 6 at the Varsity Theatre, 4329 University Way N.E., Seattle. For prices and show times, call 206-781-5755 or visit www.landmarktheatres.com.

Andrew Hamlin can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.