By Samantha Pak

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

Animal characters in children’s books may be par for the course, but certain species tend to get more pages than others.

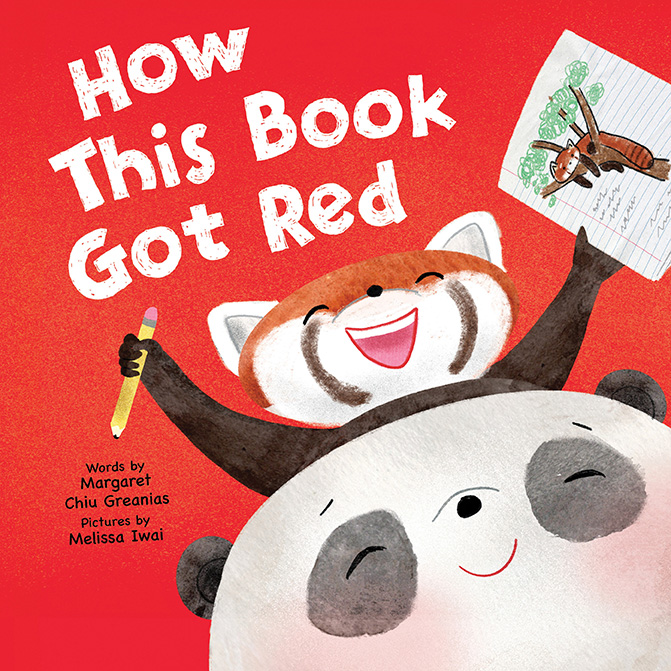

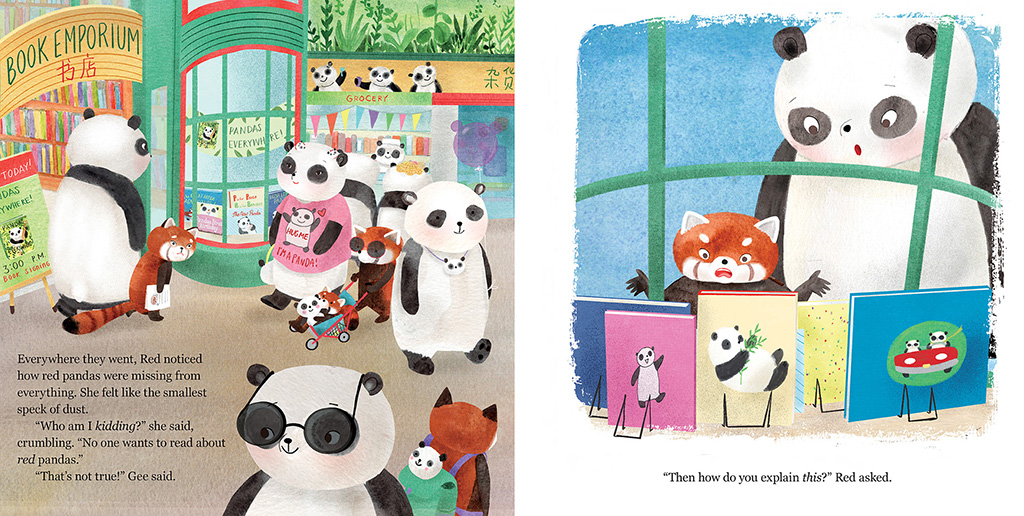

In 2015, author Margaret Chiu Greanias wanted to change that and had the idea to write a story about red pandas. Eight years later, that idea has come to fruition with “How This Book Got Red,” which was released Oct. 3. The book is the story of Red, a red panda who is excited about a new book about pandas. However, she discovers it’s only about giant pandas and red pandas have been completely left out of the story. So like Greanias, Red decides to do something about it and sets out to write a book about red pandas, with the help of her giant panda friend, Gee.

Greanias and Red weren’t the only ones who had the idea to write a story about red pandas—which are actually more endangered than giant panda bears. Greanias said around the same time she was brainstorming, Disney asked her to write a story that would serve as a prequel to their Pixar film, “Turning Red,” which also features red pandas.

“It was a weird coincidence that they happened to have this movie,” she said.

In the end, she declined their offer in order to write her own story, which is about why representation matters, with Greanias reflecting on the lack of Asian representation she saw (or rather, didn’t see) in books, and how it affected her.

“Even though I was born in the U.S., I still felt really foreign,” she said.

Humanizing a community through representation

Greanias said in stories about different types of people, readers can put themselves in characters’ shoes and empathize with them. And when you can empathize with someone, she said, you humanize them. But in the opposite case, when people are not represented and invisible, it makes it easier to not see them as fellow human beings and that’s when prejudice and racism—such as the kind AAPIs experienced during the pandemic—happen.

“It wouldn’t have been so easy to dehumanize Asians,” Greanias said about why more AAPI representation is needed.

Melissa Iwai, the book’s illustrator, agrees. Like Greanias, she grew up not seeing herself represented in the media. Watching shows like “The Brady Bunch,” Iwai knew she could never be on a TV show like that—at least not related to the Bradys. It wasn’t until she visited Hawaii, where her parents grew up and Asians are the majority, that she saw people who looked like her on TV. In this case, it was a McDonald’s commercial.

Iwai, who likes to add Asian representation to the books she illustrates (even if it isn’t an Asian story), was brought on board to illustrate “How This Book Got Red” through her agent and the book’s publisher, Sourcebooks. But her involvement almost didn’t happen.

“I was so busy at the time that I almost didn’t take it,” Iwai admitted.

But after reading Greanias’ manuscript, she was sold.

“Thank goodness,” Greanias said after learning of Iwai’s journey, adding that she was very excited to see how Iwai illustrated her vision for the story.

“It was amazing. It was better than I could ever imagine.”

A message for readers young and old

While she could have written a story featuring human characters, Greanias said using animals makes the message softer, more approachable, and more accessible. Because even though “How This Book Got Red” is about the lack of Asian representation, Red’s story could relate to any group of people who do not feel represented. In addition, Greanias added that kids are good at empathizing with animals, which is a good way to make the message applicable.

Greanias said she hopes that both kids and adults will gain a deeper appreciation about why representation matters. She hopes that kids will become more conscious about what they read and, if they don’t find the types of books they are looking for, she hopes they feel empowered to ask for it. Both Greanias and Iwai hope to inspire children to write or draw their own stories—just like Red does.