By Stacy Nguyen

Northwest Asian Weekly

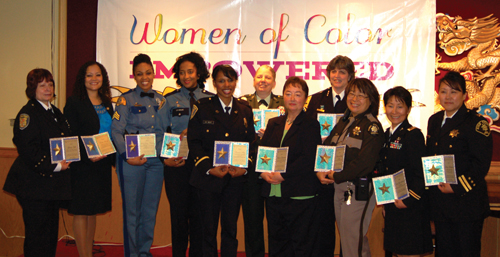

Women of Color Empowered honorees, from left: Linda Hill, Erika Hunter, Monica Hunter-Alexander, Denise “Cookie” Bouldin, Carmen Best, Traci Williams, Hisami Yoshida, Colleen Wilson, Annette Louie, Janice Mano Lehman, Lisaye Ishikawa (Taylene Watson not shown.) (Photo by Rebecca Ip/SCP)

“I grew up in Louisiana. North, rural, segregated Louisiana. It wasn’t in the cards for me to be standing here, talking to you,” said Taylene Watson, director of social work at Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System. <!–more–>

In 2006, Watson was named the National VA Social Worker of the Year, one of the highest honors in her field.

“My first struggle actually came from a traditional Chinese family,” said Capt. Annette Louie from the King County Sheriff’s Office. “It’s not expected for Asian females to be in this position or to even be in law enforcement. My father expected his children to get their education and to get into either accounting or engineering. I didn’t follow that path.”

Today, Louie has 31 years in law enforcement under her belt and is assistant police chief for the City of SeaTac.

“My parents are from the Dominican Republic,” said Erika Hunter, program analyst for the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)’s Seattle Field Division. “My parents spoke Spanish in the home. They didn’t speak any English. … And I showed up to class one day, and people were speaking a different language. So I ended up coming up in school taking English as a Second Language. With that, I had lots of difficulty reading and had serious reading comprehension issues.”

Hunter read and wrote for hundreds and hundreds of hours, while attending community college in south Florida, trying to catch up. In 2000, at only 22, Hunter became platoon leader of Bravo Company, 2nd platoon, 29th signal battalion, at Fort Lewis.

“I grew up in Chicago, in the projects,” said Det. Denise Bouldin, from the Seattle Police Department (SPD), “where when you go outside your door, and you get approached by drug dealers, [see] crime, and folks trying to get you into prostitution.”

“But thank God I had a strong mom. We were those kinds of kids who were scared of our parents,” Bouldin said. “And so we had to be in before the sun went down. Before the street lights came up, we had to be in the house. I used to hate that because my friends would come out, and I wanted to hang with my friends. … But I was so glad I had strong parents. … Because a lot of my friends ended up in jail, cracked out on drugs. A lot of them ended up dying, as well.”

Today, Bouldin is affectionately known throughout Seattle as Detective Cookie. She is the founder of Detective Cookie’s Urban Youth Chess Club.

Watson, Louie, Hunter, and Bouldin were four of the 12 honorees at the Women of Color Empowered Luncheon on May 13, at New Hong Restaurant, in Seattle. The event honored women who have significant accomplishments in law enforcement and the military.

The path to an unconventional career

Bouldin has five brothers. Growing up, she watched the police officers in her neighborhood harass her brothers, solely because they were young Black males. As a child, the people around her said they hated the police. It became a feeling that Bouldin also internalized.

“At first, I didn’t know why. I just hated them because everyone else hated them, which is so unfair — to hate someone and you don’t know why you hate them,” said Bouldin, in hindsight. “And then to hate everyone in that group because of one person. It’s so unfair.”

In high school, Bouldin had dreams of becoming a dancer and teacher — and she did become a dancer for a while. But her goal of teaching was replaced with another calling after one pivotal meeting.

“I met the police officer at my school, and he was so different from everyone else I met on the street,” said Bouldin. “He was so nice. He talked with us. Just meeting that officer, I decided right then that I wanted to be a police officer.”

Despite low SAT scores, Hunter still dreamed of joining the military, partly inspired by her father, who joined the military shortly after she was born to provide his family with a better life. She said things turned around for her once she realized that she needed a goal.

“I guess my greatest weakness ended up turning into my greatest strength,” she said. “I looked up what I needed to do to become an officer of the United States Army. Because I was so behind in my reading … I had to catch up to the status quo to even get into college.”

Not only did she get into college, she flourished. One of her first jobs was as a DEA contractor, a position that required lots of analysis, reading, and writing — tasks that used to paralyze her. Today, she is principal adviser to the special-agent-in-charge in the Seattle field division, which covers four states.

Like Hunter, Watson also believed that education and family were key. To the surprise of many people, she became valedictorian of her high school class. Though her mother had no money saved for her education, Watson worked her way through college.

“My mother taught me not to accept the definitions that were given to us,” said Watson. “If you know anything about segregation in the South — as a child, it can be pretty scary. But my mom was very brave, and it turned out, I was just like her.”

Watson got a job offer from the VA right after graduating. Her first position was in Michigan, in the winter, she said, with a laugh.

After Bouldin moved to Seattle and joined SPD, people mocked her. “They thought that I was there for a joke, some of the guys.”

Despite the taunts, she made it through and decided to keep a positive outlook.

“I was the only Black female on the street at that time. It was kind of different. It was different for people to see. But I decided to be like that officer at my high school. I was going to be out there. I was going to meet the kids. I was going to interact with the kids. And I’m going to be a part of them.”

Challenges being in a man’s world

Women in law enforcement or the military often face a subtle kind of discrimination. Many report being sometimes held to a different, perhaps stricter standard, than their white male counterparts.

“When I started my profession, there weren’t many law enforcement supervisors who were female, and there weren’t many supervisors who were people of color,” said Capt. Lisaye Ishikawa, from King County Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention. “So you have to look within to get yourself to where you want to be. One of the things I came across was, ‘Is she here because of the minority quota?’ ”

Currently, Ishikawa works with command staff and administration as part of the management team to serve in a leadership capacity as a jail shift commander.

“Being a woman of color in a traditional white male organization, some peers think that they worked really hard to get where they are, whereas I got where I am because of my gender or my race,” said Hisami Yoshida, correctional program manager at Stafford Creek Corrections Center. “Also, those I supervise can be more critical of me than their white superiors. I think that is what a lot of women experience in [these roles].”

In 1998, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) published a study, “The Future of Women in Policing: Mandates for Action.” The study surveyed 800 IACP members and revealed critical information about women in policing — that women were underused and undervalued in law enforcement, though the number of women in law enforcement was growing.

At the same time, the study also recognized that there are strengths in having female police officers. “[The IACP] found there are very unique qualities that women have in the profession. They said that women possess special communication, verbal, and interpersonal skills,” said Lt. Carmen Best from the Seattle Police Department, where she is responsible for overseeing personnel assigned to community outreach, youth outreach, school emphasis, media response, the citizen’s police academy, and demographic advisory councils, among other things.

At other times, the challenge that women face in law enforcement isn’t just interpersonal — it’s physical.

Col. Janice Mano Lehman, who started her career as a nurse and currently works at Madigan Army Medical Center at Lewis-McChord, bluntly summed it up. “I’m short. And I’m a female.”

Mano Lehman stands at about 5 feet with a small build. At the luncheon, she recounted a time during her training when she had to carry a 60-pound bag for miles.

“One of the police tests that I took back then was called the step test,” said Louie, who is about 5’3″ and who has worked as an advanced training unit instructor and special assault unit detective. “The step was 30 inches high, and you had to step up and down that silly thing for five minutes as you were monitored. That’s a pretty big step for me. That was 30 years ago. They’ve changed that since then.

Now, the test is a little more appropriate for the job,” she said, with a smile.

Sgt. Monica Hunter-Alexander, from Washington State Patrol (WSP), faced an obstacle in the form of tradition. With about 4.5 years under her belt, she thought she was ready to take the exam to become a sergeant. However, tradition dictated that she wait 10 years before taking the exam. People told her she wasn’t ready, something that didn’t sit well with Hunter-Alexander.

“I was a young mother with a young son, and I wanted to be a good role model for my son. I wanted to do a lot of things,” said Hunter-Alexander, who took the exam early and passed.

Master Sgt. Traci Williams has had an esteemed career in the military, which she joined at 30 years of age — later in life than some of the other honorees, but Williams saw it as a calling.

She has been deployed to Haiti, Germany, Kosovo, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

In Afghanistan, Williams was faced with a certain cultural difference. There were certain inequities between males and females. Due to her position of power, Williams was about to do something about it.

“I happened to be in charge of dispersing all the donations that came from the United States out to hospitals and out to schools. Being female, being in charge of all that, I’d have to go and talk to the imams, the elders, and see how they’d give our donations. If they weren’t allowing girls to go to schools, I wasn’t going to support that. If they were not allowing females in hospitals, I wasn’t going to support it.”

“We’d take 80 soldiers every week,” she continued. “Convoy out there. Give this stuff away. It was fantastic. Afterward, the soldiers played with kids. It was very, very rewarding.”

Words of wisdom

“Being a supervisor, I also look at it like, I have to honor and respect people who take responsibility for their actions and learn from their experience,” said Louie. “I have to make sure that my decisions and actions are fair and consistent, and that I have done the right thing. If I make a mistake, I own it.”

“I believe that I came to this position as much by chance as anything,” said Chief Colleen Wilson, from the Port of Seattle Police Department. “But you take opportunities as they come. I’ve had blessings. My mother taught me to respect everyone, no matter who they are, or where they came from. … She taught me that if I was stronger or smarter, that it was not a privilege, but an obligation.”

“It’s important to know who you are,” said Linda Hill, Native American Liaison for SPD, who also spoke a bit about the conflict of identity she felt after the fatal shooting of American Indian John T. Williams last year by an SPD officer. “It’s important to stay in contact with your family, your people. … I’m proud to serve my communities, all of them, at the same time.”

“I truly believe that it’s possible to change an organization,” said Yoshida. “I believe we have lots and lots of examples of how that has happened. Just the very fact that all of us, as women of color, are here today, is a change in how our nation and our organizations have been, through decades and decades. It’s possible to change that even more. As women of color, we have a responsibility to actively try to make that change. … maybe we change our organization, and maybe in that process, we change the world.”

Each honoree was given a $45 gift certificate from New Hong Kong Restaurant and flowers from the Northwest Asian Weekly. Parella Lewis, weather anchor and Washington’s Most Wanted correspondent for Q13 FOX News, was master of ceremonies. ♦

For more information, visit womenofcolorempowered.com.

Stacy Nguyen can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.

It’s good to hear about other females who are in law enforcement/corrections. I have been in corrections for over 12 years on the otherside of the mountains and we don’t seem to have much diversity, but appreciate when I see women of color are included! Love the article!