By MARSHA KEEFER

Beaver County Times

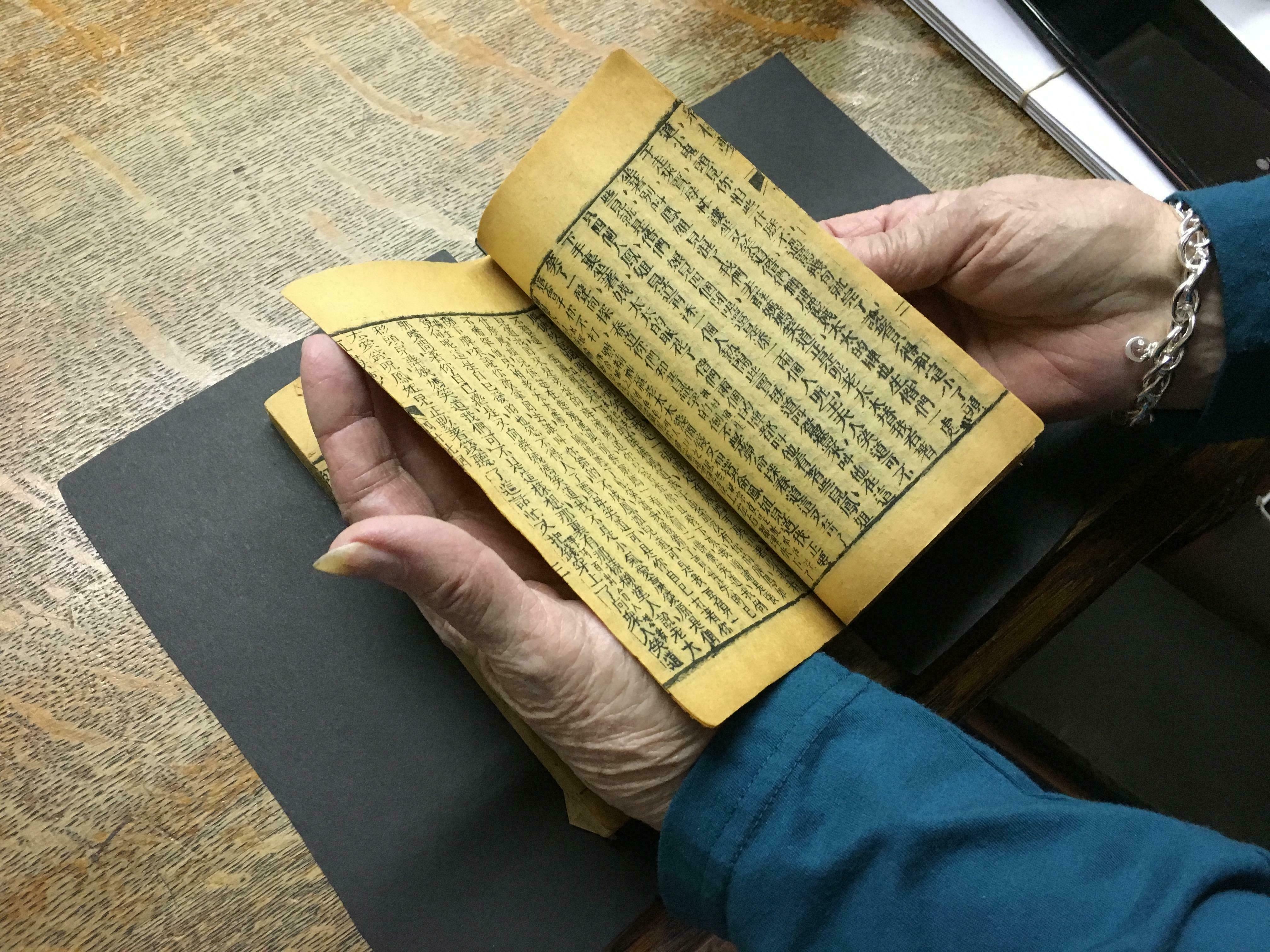

A copy of “The Story of the Stone/A Dream of Red Mansions,” written by Cao Xueqin in the mid-18th century during the Qing dynasty. (Marsha Keefer/Beaver County Times via AP)

BEAVER FALLS, Pa. (AP) — The fragile, yellowed, woodblock manuscript is in relatively good condition, remarkable considering its age and the location where it was found: in a dark, dank storage closet in the Beaver Falls Historical Museum in the bowels of the Carnegie Free Library on Seventh Avenue.

It’s garnered worldwide attention, especially in the Chinese community, as it’s considered to be a masterpiece of Chinese literature — on par with Shakespeare in the West.

“The Story of the Stone/A Dream of Red Mansions,’’ written by Cao Xueqin in the mid-18th century during the Qing dynasty, still is required reading for all Chinese. The classic — a daunting tome with close to 400 characters and written in vernacular Chinese, first circulated in woodblock manuscripts until its first print publication in 1791.

The fictional work, largely a love story, chronicles the rise and fall of an aristocratic family in Beijing.

How the manuscript on rice paper, estimated to be at least 175, possibly 200, years old, came to Beaver Falls is fascinating history. But equally so is the story of its discovery in the historical museum.

Betty Anderson of Brighton Township is director of the Beaver Falls Historical Museum, charged with acquisition and preservation of collections and artifacts. Basement archives — filling five rooms, two of which are storage — have about reached capacity, she said.

“We collect everything,’’ Anderson said, much of it donated treasures from people cleaning out attics and basements or gifted by estates.

“I’ve been gifted the last two to three weeks at least 40 boxes of things and articles. They’re everywhere here.’’

About five years ago, she went into one of the storage rooms — a room that had not been entered in at least 50 to 60 years, she said.

“I peeked in it 30 years ago. I couldn’t get in,’’ she said, so stacked it was with boxes.

Anderson doesn’t remember what she was looking for this time, but reached into a box and felt something soft: seven chapters of a rare, woodblock manuscript bound in tightly woven thread.

Of course, with it being written in Chinese characters, she had no idea what it was or its historical significance, but thought it would complement the museum’s Beaver Falls Cutlery Co. collection.

The manuscript — with an intrinsic value that’s priceless, she said — was simply displayed on a shelf in a locked, glass case alongside knives, forks, photographs, illustrations and other artifacts pertaining to the cutlery company that operated in the city from 1867 to 1886.

But first, Anderson, with remarkable encyclopedic recall, tells a riveting story about how Chinese arrived in Beaver Falls.

Like most immigrants, Chinese workers came to America to escape economic hardship and build a better life for their families. Many first came to California to mine gold after the precious metal was discovered in the Sacramento Valley in 1848.

When the Gold Rush ended in 1855, many stayed on to help build railroads across the country, including the First Transcontinental Railroad. About a decade later, 255 Chinese laborers were contracted to work in Beaver Falls.

Beaver Falls Cutlery Co. was an enterprise of Harmonists at Old Economy in Ambridge. The society first established a company in Rochester in 1866 to make pocket knives, expanding a year later in the south end of Beaver Falls to not only produce pocket knives, but tableware knives, kitchen knives and forks. Handles alone are works of art, Anderson said, many formed of ivory and mother-of-pearl.

A labor dispute culminated in a strike in 1872. Company officials reached out to John Reeves, a prominent citizen and banker in town. Reeves first traveled to California, hoping to entice Chinese to fill jobs of striking workers.

“They didn’t drink and they worked hard,’’ Anderson said, willing to work for lesser wages.

When they refused to uproot and travel east, Reeves found willing Chinese laborers in Louisiana who were finishing work on a railroad there.

Contracted for five years, they were paid one gold coin a day for 30 days.

They traveled by rail — about a hundred men at a time, Anderson said — arriving at the former New Brighton-Beaver Falls train station, and then walked four blocks to the cutlery.

Understandably, striking workers weren’t hospitable.

“Some of the men were angry because they were going to lose their jobs,’’ Anderson said.

When the train arrived, some grouped at the station, but before any trouble ensued, Reeves and a constable “kept them at bay,’’ she said.

Two interpreters accompanied the newcomers who were housed in a “beautiful, big stone building’’ called Patterson Manor — about 50 feet from the factory and where today stands Beaver County Fruit Co.

Anderson estimated four to eight workers slept in a room, perhaps in bunks. They discarded pillows given to them, preferring to rest their heads on wood blocks instead, she said.

Though Chinese workers largely kept to themselves, they were a curiosity to townspeople.

“They were in awe,’’ said Anderson. “People came just to look at them.’’

Men dressed in silk clothes, wore sandals and tied their hair in pigtails.

They built small, wooden structures adjacent to the manor where they laundered clothes and roasted pigs over fire pits.

One story has it that two roasted pigs dangling from a pole were “marched right into the superintendent’s office of the cutlery and put on his desk,’’ Anderson said, given as a gift.

Many of the churches in town “would not deal with them,’’ she said, afraid that if their pastor befriended the foreigners, they’d lose worshippers.

But one church was accepting — a Presbyterian church on the end of Eighth Street, a church since torn down.

“They brought them into the church, fed them, started to talk with them, teach them English,’’ said Anderson.

One worker fell in love with a girl who tutored him, but the relationship abruptly ended when “she was sent away,’’ said Anderson.

During their five-year stay, 10 workers died and were buried in a cemetery on 27th Street, which today is a playground. Years ago, their bodies were exhumed, sent to Louisiana and then to China, said Anderson.

“Mr. Reeves was very respectful of what happened to them,’’ she said.

A third interpreter would come to Beaver Falls, a man of means who brought his wife. It’s believed she’s the one who brought Xueqin’s manuscript of “The Story of the Stone’’ to Beaver Falls.

Anderson said she has no idea how it wound up in a dusty box in the museum’s closet.

It took Xueqin 40 years to write the book, she said. He wrote intermittently, a few chapters at time that would be bound, copied and shared freely with friends and family.

Xueqin died in 1763 before finishing his book. He wrote 80 chapters and it’s said 40 more were written by Gao E. Its first print publication was in 1791.

Penguin Classics, publisher of global, classic literature, translated and published five volumes of “The Story of the Stone’’ in 1973, consisting of more than 2,000 pages.

‘An absolute treasure’

A few years ago, a young man and woman of Chinese ancestry visited Beaver Falls Historical Museum from Kent State University in Ohio. Anderson thought they might be interested in the cutlery display and directed them to the showcase.

The man leaned in, looked at the manuscript and told Anderson it was displayed upside down, she said laughing.

She unlocked the case and handed it to him to look at more closely.

“You have one of the four most important books in China,’’ he told her. Those words still bring tears to her eyes at the realization that “we have something so precious,’’ she said. “It’s just amazing.’’

Anderson knew she’d have to research the book’s history.

But first she had to preserve and protect the fragile manuscript. She and staff volunteers carefully copied approximately 300 pages of their seven chapters. The original, encased in special archival materials that limit exposure to light, is now stored in a bank vault only to be viewed by appointment.

“I want people to see it,’’ she said. “It isn’t that I’m hiding it. I have to preserve it. It is gorgeous and it is so rare.’’

Anderson’s research into the manuscript was easier than thought thanks to another visitor. He, too, was affiliated with a museum — she doesn’t remember what or where — and asked permission to photograph the cutlery display.

She agreed, though at the time said she had “no clue what he did with the information.’’

He shared it online, which attracted the attention of a trio of Chinese researchers whose mission is to preserve their history.

About a year ago, Qian “Cathy’’ Huang of New York contacted Anderson, having seen the online post.

“She asked 100 million questions all through the year, on and off,’’ Anderson said, and also received a copy of the manuscript, which she took to Beijing Normal University. A scholar there authenticated it.

“He was excited to death about this,’’ Anderson said.

Last fall, Huang and her colleagues Chang Wang, an attorney from Minnesota, and Wei Ming Yao of Pittsburgh, visited Beaver Falls Historical Museum to see the original manuscript and other artifacts of Chinese who worked at Beaver Falls Cutlery Co.

Wang told Anderson that finding the manuscript “is like finding a Shakespearean manuscript.’’

They wanted to see everything — where the train station, company and mansion were, the Presbyterian Church, the cemetery and other parts of the city and county — and produced a documentary that’s posted on their Facebook page and YouTube.

Anderson said likely there are other Xueqin manuscripts in existence, but “this is the first one people can come and see. The others are in private collections.’’

She pulled an envelope from her desk and removed a handwritten note card from a Chinese couple in California who saw the documentary and love the book.

This came in the mail, she said, along with a donation to the museum: “What you, Mrs. Anderson, and your colleagues did, still doing, means so much for not only those early immigrants, but more for the new generation of Chinese immigrants. You’re the warriors who fight for history to be remembered to remind us who we are and where we came from … What you are doing is to preserve the essentials of America. Keep going.’’

“It’s wonderful. It’s very kind,’’ she said, but quickly added it isn’t her intent to make money off the manuscript.

However, she hopes it spurs tourism and more visitors to Beaver Falls and the museum.

“I do not know if it will be a tourist thing. I do not know if there will be an influx of people to come and see it. We will welcome it,’’ she said.

Soon, Anderson plans to host an open house so the public can view it.

“This is a find. An absolute treasure. Amazing. Who would have thought?’’