By James Tabafunda

Northwest Asian Weekly

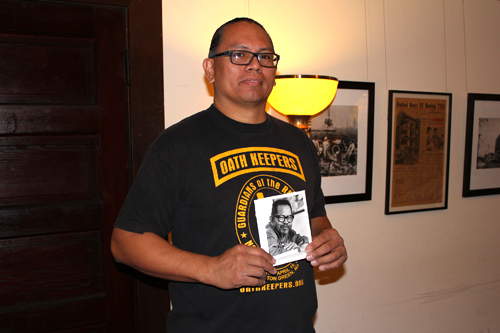

Johnny Itliong poses with a photo of his father, labor organizer Larry Itliong, while visiting the Panama Hotel in Seattle Nov. 16. (Photo by James Tabafunda/NWAW)

As with justice, a rightful place in U.S. history delayed is that place denied.

After the Immigration Act of 1924, agriculture companies recruited Filipinos among other Asian immigrants to work in the fields. Mexican immigrants were also hired, and Cesar Chavez rose to become one of the most honored leaders of American farm workers — the Cesar E. Chavez commemorative postage stamp was issued on April 23, 2003.

Johnny Itliong, 48, visited the Seattle headquarters of the Filipino American National Historical Society on Nov. 8 to remember another leader in the farm workers’ movement who received little credit — his father, Larry Itliong. He also commemorated what would have been his father’s 100th birthday on Oct. 25.

“Larry was a very striking figure. He was a warrior,” said Magdaleno M. Rose-Avila, director of Seattle’s Office of Immigrant and Refugee Affairs.

Johnny Itliong said, “The one thing I’m trying to do with my father’s legacy is to get the truth out there.”

He makes 40 to 50 public appearances each year, mostly in California, to speak about his father’s legacy and life’s work, which he says have been ignored by history, the people, and the government. Cesar Chavez received a 2011 presidential proclamation designating March 31 as Cesar Chavez Day.

A chef at VenTiki, a restaurant in Ventura, Calif., Johnny Itliong is also the executive director of the Larry Itliong Foundation on Education, an organization created “to educate the community, schools, and students on the contributions of Larry D. Itliong.”

“I’ve been doing this for about 26 years now,” he said. “The year 2010 is when things really happened. The key thing is Melissa Aroy and her documentary ‘The Delano Manongs: Forgotten Heroes of the United Farm Workers.’”

Born in San Nicolas, Pangasinan, Philippines, Larry Itliong immigrated to the United States in 1929, raised seven children, and spoke many languages. “I was told by someone that Larry never met a stranger. He treated everybody like a friend,” said his son.

From the 1920s to the 1960s in California, Filipinos picked lettuce in the Salinas Valley and asparagus in the Stockton area despite the discrimination they faced as immigrants. But it was when they picked grapes in the San Joaquin Valley that Larry Itliong made history.

Itliong and the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), a labor union made up of mostly Filipinos, demanded the same pay as other higher-paid farm workers and better living conditions, however, their requests were turned down.

On Sept. 8, 1965, Itliong led 1,500 Filipino workers to go on strike. They refused to leave their labor camps and report for work in the vineyards of Delano, a small rural town 142 miles northwest of Los Angeles.

As the growers tried to recruit replacement workers to pick the grapes, “Cesar Chavez was invited [to help], asked to join,” Johnny Itliong said. “They butted heads because Larry Itliong was a true labor union organizer.” In Matt Garcia’s book, “From the Jaws of Victory,” he wrote, “Many tell the familiar story of how a reluctant Cesar Chavez was drawn into the strike by the more radical, union-oriented AWOC members, especially Larry Itliong.”

The United Farm Workers of America (UFW) referred all questions concerning Itliong and the strike to Marc Grossman, communications director of the Cesar Chavez Foundation. He said, “At first, Cesar was worried. He had spent more than three years painstakingly building the NFWA (National Farm Workers Association) from the ground up through grass roots organizing and thought it would be many more years before his young independent union was ready for a major field action. … Cesar, Gilbert Padilla, Dolores Huerta, Richard Chavez and the other early NFWA leaders felt they didn’t have a choice except to accept the invitation from Larry Itliong and AWOC to join the picket lines.”

Eight days after the Filipino farm workers voted to strike, Chavez called a meeting with NFWA members at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church Hall in West Delano. “There was a unanimous vote to join the strike, which happened on Sept. 20,” Grossman added.

In 1966, Bill Kircher, the national director of organizing for the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), negotiated the merger between Itliong’s AWOC and Chavez’s NFWA. On Aug. 22, 1966, Larry Itliong stood with Cesar Chavez for a Jon Lewis photograph with the charter granted to their United Farm Workers Organizing Committee AFL-CIO (UFWOC).

After five years of the Delano Grape Strike and a UFWOC-led nationwide boycott of grapes, California grape growers yielded to the farm workers’ demands, including higher pay, better working conditions, and collective bargaining rights on July 29, 1970. The strike forced agriculture companies to recognize farm workers’ right to form and join a union, a historic change in the balance of power.

Itliong resigned from the UFWOC on Oct. 15, 1971, and the UFWOC received an AFL-CIO independent charter with the new name UFW in February 1972.

“We have to write our own histories,” Rose-Avila said. “We can’t allow other people to write them.”

Johnny Itliong has more than 2,000 documents about his father, and continues to research and gather information for an upcoming book. “We need our heroes,” he said. “We have them pushed aside and marginalized, treated like second-class citizens for too long.”

Larry Itliong passed away on Feb. 8, 1977. He died of Lou Gehrig’s disease. (end)

For more information about the Larry Itliong Foundation on Education, visit www.facebook.com/johnny.itliong.

James Tabafunda can be reached at info@nwasianweekly.com.